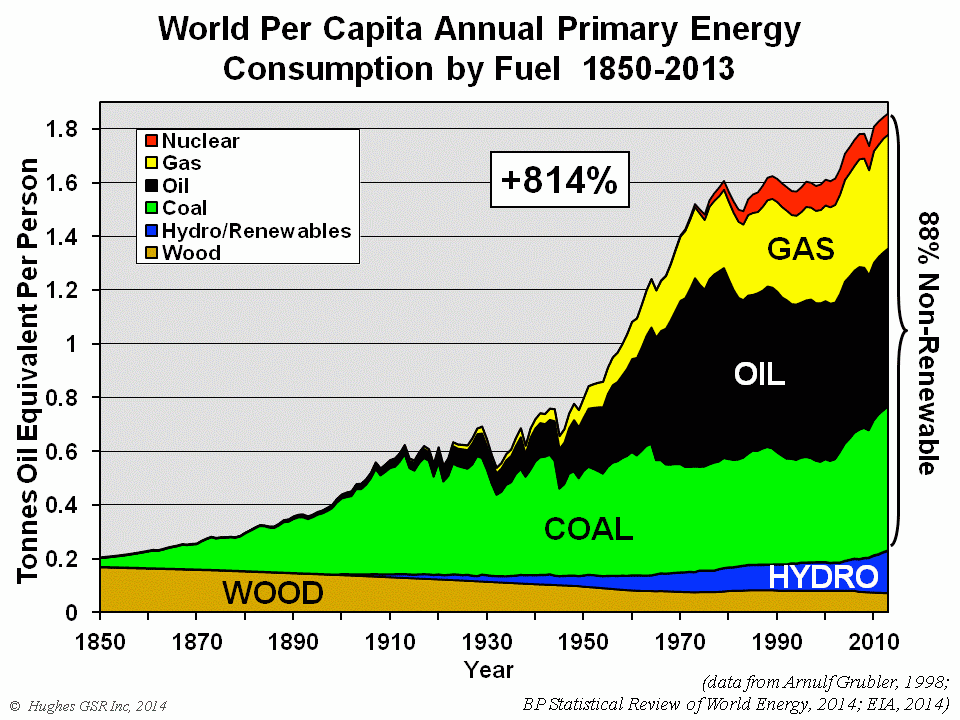

Somewhat naively, I used to think that the only thing that mattered for a sustainable future was the price point of energy from renewable sources. With rising prices for fossil fuels (primarily oil) and falling prices for renewable energy (due to efficiency improvements) it was only a question of time before the big switch was coming. In fact, recent news of

Germany's energy giant EON retiring its conventional energy business to focus on renewables and power distribution seemed to be a clear indicator of this mechanism at play.

However, there is more to this story. In a recent quarterly newsletter, GMO's Jeremy Grantham discusses the beginning of the end of the fossil fuel revolution (starting page 12 in the

Q3-2014 issue). I am a big fan of Grantham's data driven and common sense review of market mechanisms. Despite the recent price drop due to short lived US fracking sources and OPEC response to it, the times of cheaply available oil are over. The debate about

peak oil, the point at which maximum possible oil extraction is reached, and oil subsequent depletion, at which oil reserves are used up faster than new ones are discovered, seems to have been settled in recent years. It is mostly the point in time for the peak to occur that seems debatable, but even that is generally placed within a decade or so. I recommend a look at part one of the

transition handbook or the

Post Carbon Institute to get a deeper understanding of the details.

So why does this matter so much? Can't we just switch over to eternally affordable renewables if we need to? Here is where

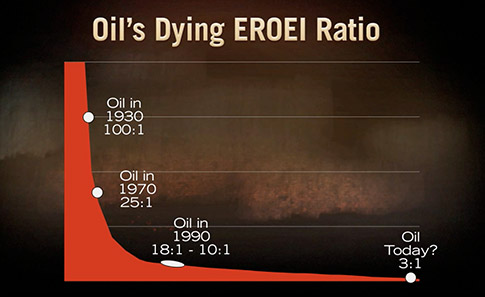

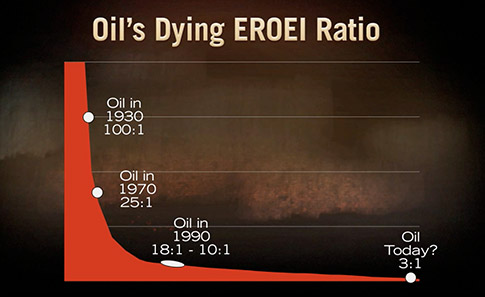

EROI (also often called EROEI) comes in. The "energy return on investment" is crucial to our current lifestyles. In the early oil days, an investment of $1 would have returned $100 worth of energy (an EROI of 100). In recent years, this has steadily declined as oil is much harder to come by. In some scenarios, we are reaching almost negligible ROI on oil extraction.

More so, if energy was once available at, say, $10, and the value it created was about $200 (a low boundary in Grantham's research), then our society benefited from an energy surplus worth $190 on each barrel extracted! It is this surplus that fueled our growth oriented, wealthy lifestyle. All sorts of convenient uses of oil were possible due to this surplus.

The second key element here is what we do with this value. If we use a barrel of oil as fuel to operate heavy machinery, one man can do the work of hundreds hence adding significantly to our level of prosperity. If, however, the same barrel is going to low value uses (e.g. throw away plastic wrappings, unnecessary transportation of goods, inefficient energy use, etc.), it does not add to our level of prosperity. One could argue that continued reduction in EROI will eliminate low level uses of energy sources.

Now, back to renewables. The question is not whether we can replace our conventional energy sources with renewable ones in a short enough time frame. This switch has to happen for climate reasons alone and will be one of the largest challenges mankind has faced so far. And, according to David MacKay's research

"Sustainable energy - without the hot air" , a quiet improbable undertaking in itself.

But even if we pull it off, renewables as it stands have a

radically different EROI than fossil fuels in their hayday. It takes quite some energy to produce solar panels, so their return is maybe 7:1 (outside of the interesting concept of "

solar breeders"). Hydro is the strongest contender, but even the best estimates do not go over 40:1 and it comes with limited scalability of hydro locations. Wind energy might lie somewhere between that with 18:1. Given that our growth based economies fundamentally depend on high EROI and that the return for fossil fuels is not only dwindling but the resource itself is rapidly depleting, we have to seriously think about the implications for our global economic system and our consequently our daily life styles.

In summary, instead of just looking at how we can quickly increase our percentage of renewable energy sources as part of our overall usage, we need to aggressively become more efficient in all forms of energy use and eliminate low-value uses to preserve the crucial high-value uses that support our quality of living. It is very questionable to me if our current consumer societies can be sustained with quickly dwindling fossil resources. That party is simply over.

----------------------

Some reading material: